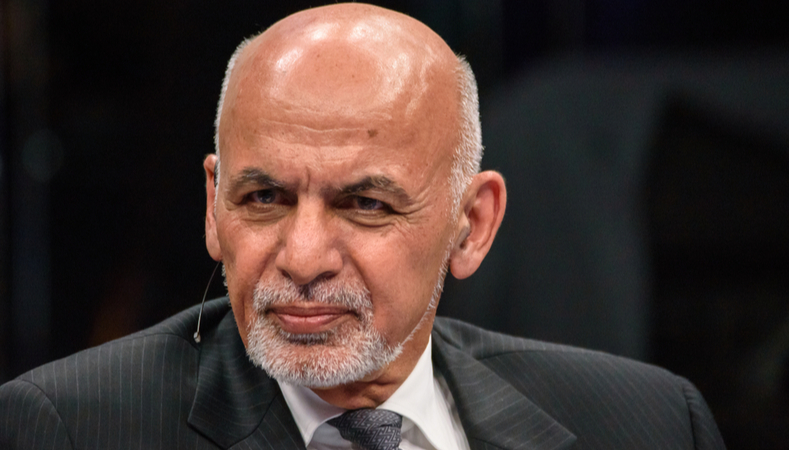

Who is Ashraf Ghani, the foreign president who failed to transform Afghanistan?

The world will remember him for leaving his country. He left without any announcement. Someone thinks that he betrayed Afghanistan, that he should have defended his country to the end. He said he tried to avoid a bloodbath. But, because it had become a personal thing for the Taliban, they wanted him to resign. “I tried to persuade the Taliban, but the condition to speak with the government was that Ghani, considered the puppet of the Americans, would go away,” Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan said just a few months after meeting a Taliban delegation.

President Ashraf Ghani, elected twice in disputed elections, has experienced a showdown in recent days. “He no longer listened, he surrounded himself only with people trusted, he made mistakes,” says a senior administration official of the president. As a result, he could not take the reins of a government that were slipping through his hands, impregnated with corruption and incompetence.

His mandate was the therapeutic persistence of a country to which the Americans have pulled the plug. For many Afghans today, the president, who was “too intellectual” for Afghanistan, has disrespected everyone. Because he left before he had guarantees to protect civil society, that allied collaborators would go, that Afghanistan did not end up entirely in the hands of the Taliban. Instead, he waited till it was too late, launching televised messages about unity and struggle as if he didn’t realize that the Taliban were grabbing an outpost, a base, then a village, and eventually capitals and entire regions every day.

“My worst reading is early in the morning when I read yesterday’s death toll. Because they are not estimates, they are lives cut too soon, they denied opportunities, and there is a person, a story, a family.” So words of the now-former president Ashraf Ghani, shortly after being elected president in 2014, sitting at the same desk where the Taliban took group photos yesterday while they lowered the Afghan flag.

Were difficult days the president’s last. They were difficult years for a man who thought that Afghanistan, with the right person, could pull a treasure out of the rubble. Instead, everyone abandoned this man. He threw open the door, which was already available, at the entrance of the worst nightmare for most people who survive in Afghanistan: the Taliban. Ghani, 72, like many other international leaders, trusted the Americans. He paid a good part of his life in the United States, where he studied anthropology, always remaining tied to the university world where he taught before joining the World Bank.

A Pashtun, like the Taliban, the majority ethnic group in the country, is considered the most challenging, most aggressive, traditionalist. Throughout the Russian invasion, the civil war, and the Taliban regime in the 1990s, he was out of Afghanistan, and many considered him a foreigner. Not only that, there aren’t many Afghans with a Lebanese wife who speaks at conferences and attends events.

Someone said that she was the Gandhi – for the physical resemblance – who had not made peace with anyone. In 2001, with the arrival of the Americans, Ghani returned with the wave of accomplished and wealthy Afghans, full of goodwill and who thought they were rebuilding the country. It was not like that at all—too much corruption. Anyone would be swallowed by it, too much money pouring the Americans and ending up in the wrong hands.

He didn’t even get to the top chair quickly. His rival Abdullah Abdullah, of the Tajik ethnic group and former foreign minister with Karzai, closely marked him from the start. So when he was elected president on his third attempt, after having been Minister of Economics with his predecessor Karzai, everyone thought that was too intellectual to manage a country like Afghanistan often driven more by instinct than by reason, more by power than by utility. A corrupt and divided country. Everyone has something to demand, whether they are warlords or international actors, and are willing to do anything to get it.

Over time, a figure has become increasingly isolated due to the pressures and Taliban attacks increased in recent years. So when US President Donald Trump signed an agreement with the Taliban in February 2020, he immediately knew it was his end. Nobody had invited him. They decided game’s rules without that part of the Afghans that the Americans themselves had hitherto supported.

Then the American president forced him to free thousands of prisoners, the same ones who have commanded the troops that have conquered three-quarters of Afghanistan in recent days. The Afghans then sat down in front of the Taliban without saying anything to each other for months.

Meanwhile, foreign governments were irritated by the lack of progress; someone began to call for a change of administration. However, Ghani had over time appointed a generation of young, educated people, putting them in critical positions, perhaps too much because they had no experience. He perceived a sort of disconnect between what they wanted and the reality that surrounded them.

Ghani wanted to transform the country into an essential Asian economic hub but failed. But, in the face of failures, civil society has flourished in Afghanistan in recent years that he has not hindered. He supported the emancipation of women and, unlike Karzai, was harshly criticized for trying to close the anti-violence centers because foreigners ran them.

Now Ghani is in Oman and will probably return to his home in the United States, where part of the family that recently left Afghanistan has already moved. So here remain the real winners, the Taliban, the Iranians, the Pakistanis, the Russians with the embassy that says Ghani escaped with four cars full of money. The American front withdrew, and the new axis of Pakistan, China, and Russia opened the doors to the Taliban. “Its people will determine the future of Afghanistan,” Ghani once said in an interview, and, in the end, he was wrong here too.